- The issue of declining birth rates and an aging population is a common problem in many countries, but why is it particularly severe in China?

- The demographic dividend ended earlier than expected, making China more susceptible to falling into the "middle-income trap."

- A decrease in the child and adolescent population suggests a weakening of overall social consumption power.

Demographic change is one of the most fundamental and profound factors affecting a country's long-term development trajectory. For the past few decades, China's vast and young workforce created a demographic dividend that fueled high economic growth. However, entering the 21st century, due to the low fertility rate caused by birth-control policies implemented since 1979, combined with an increase in life expectancy, China's population structure is undergoing an unprecedented, rapid, and massive population aging process. This is not merely a change in numbers, but a systemic challenge and crisis that impacts the economy, society, finance, and even national strategy.

China's Second Turning Point: When Deaths Outnumber Births

China's population had been the largest in the world since population records began, until it was surpassed by India in 2023. According to data from the China Statistics Bureau, when the People's Republic of China was founded in 1949, the total population was approximately 540 million, accounting for 22% of the world's total population. The population in 2024 is 1.40828 billion, or about 17% of the global total.

Looking back at China's census history, seven censuses were conducted between 1949 and 2025. While the total population has continued to rise, the average annual growth rate has been declining year by year. Of particular note, the population peak arrived early in 2021, eight years ahead of the previously estimated peak point of 2029 (estimated in 2019), indicating that the speed of China's population decline is more rapid than anticipated.

Since 1950, China has experienced two periods of negative population growth. As shown in Figure 1, the first was during the Great Famine of 1959–1961, which officials attributed to abnormal climate conditions and resulting food shortages. Although the Chinese government has not released the number of abnormal deaths during this period, subsequent estimates by Chinese and foreign scholars suggest there were over 30 million abnormal deaths.

The second "more deaths than births" crossover point occurred in 2022. Subsequently, China's population has been in continuous negative growth. The speed of China's population decline is rapid; the UN's "World Population Prospects 2024 (WPP)" predicts that by 2100, China's total population will shrink to 6.2% of the global total.

China's official population statistics have long been controversial and even questioned by some scholars for being an overestimation. Chinese sociologist Li Jianxin once pointed out that the Chinese government has long held a "total number anxiety" regarding excessive population, and thus has a tendency to overestimate the population to heighten vigilance. Chinese demographer Yi Fuxian has even directly stated in multiple articles that the official population figures published by China may contain as much as 130 million "inflated" data.

These doubts are not unfounded. For example, in 2000, the number of births announced by the census was 13.79 million, but the figure released by the National Bureau of Statistics was 17.71 million, a difference of nearly 4 million people. Furthermore, official population statistics have undergone multiple major reassessments and revisions. For instance, a data correction in 2021 for the 2020 census revised the number of births between 2011 and 2019, adding about 10 million people. This back-and-forth fluctuation in statistical figures inevitably raises external doubts about their accuracy.

The recent COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated the problem of distorted demographic data. During the pandemic, China concealed the true death toll and its impact on the social economy, and stopped publishing several key statistics, including the unemployment rate, commercial confidence index, and others. In the 2022 Shanghai Public Security data leak incident, a hacker publicly offered to sell personal data of 1 billion Chinese residents. Outside speculation suggests this might be the true population number for China, showing a significant discrepancy with the official claim of 1.4 billion. This lack of transparency and distortion in statistical data not only affects external objective judgment of China's social economy, but also leads to serious misjudgment in formulating internal policies related to retirement, healthcare, and education, which in turn impacts the country's long-term development.

A Nation "getting old before getting rich"

Population aging is a universal global phenomenon, but unlike many developed countries, China's population aging presents a structural predicament of "not yet rich, already old".

An important indicator for measuring population aging is the proportion of the population aged 65 and over. When this proportion exceeds 7%, the society is defined as an "aging society"; over 14% as an "aged society"; and over 20% as a "super-aged society". China entered an aging society in 2000, an aged society in 2022, and is expected to enter a super-aged society by 2030.

Observing other developed countries, it took France 115 years and Sweden 85 years from the start of the decline in total fertility rate to the entry into an "aging society". China, however, only took 36 years. This speed of aging is historically rare.

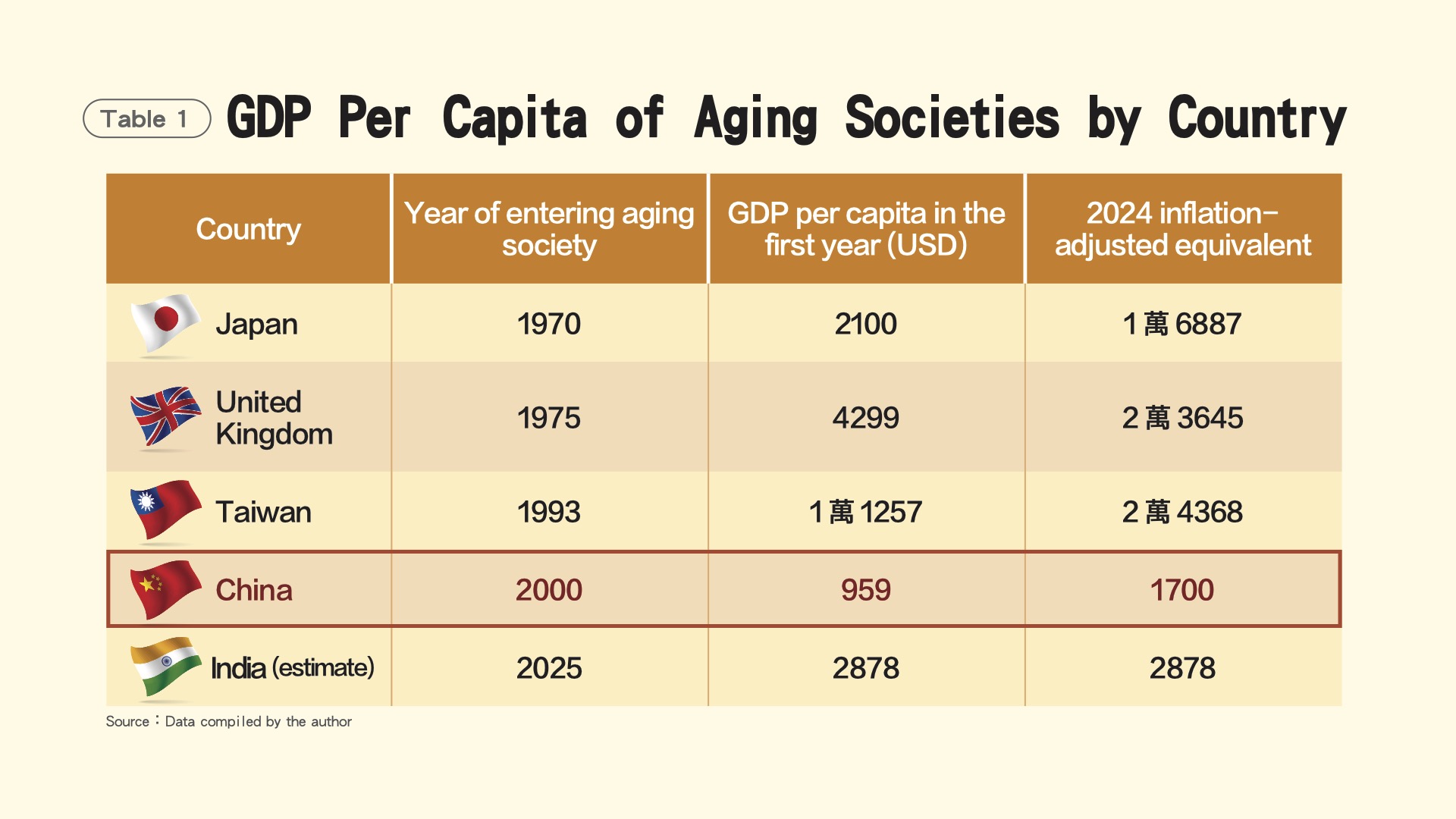

More crucially, when other developed countries entered an aging society, their per capita GDP had already reached a considerable level. For example, when Japan entered an aging society in 1970, its per capita GDP was $2,100 (equivalent to $16,887 in 2024). When Taiwan entered an aging society in 1993, its per capita GDP was $11,257 (equivalent to $24,368 in 2024). In contrast, when China entered an aging society in 2000, its per capita GDP was only $959 (equivalent to $1,700 in 2024). This situation of "getting old before getting rich," where the country enters an aging society before its economy is fully developed and national wealth is sufficiently accumulated, will bring hidden worries for China's national power.

The root cause of China's "getting old before getting rich" status primarily stems from the long-term "one-child" family planning policy. Before the one-child policy was implemented, the Chinese government had already implemented birth control policies in various provinces. However, in the 1970s, the "System Dynamics Model" used by the team of missile expert Song Jian simulated fertility rates and argued that if the one-child policy were not implemented, China's population would reach 4.26 billion by 2080, and economic growth would be offset by overpopulation. Consequently, China strictly implemented the one-child policy starting in 1979.

The one-child policy successfully capped the number of births and lowered the fertility rate. As can be seen in Figure 2, China's total fertility rate fell below the replacement rate of 2.1 as early as 1991. In other countries, birth control policies should no longer be implemented once the fertility rate falls below the replacement rate. However, this policy, which demographers called "the largest social engineering project in human history," was only formally abolished in 2016, having been implemented for a total of 36 years.

Subsequently, with the number of births nearly cut in half, China successively introduced "two-child," "three-child," and other pro-natalist policies. But due to the social and cultural inertia caused by the long-term restriction on births, as well as recent economic pressures and the impact of the pandemic, the public's willingness to have children has plummeted. The total fertility rate in 2023 was only 0.99, lower than that of the United States and Japan.

The Consequences of a Graying Nation

The 36 years of the one-child policy caused a rapid rise in the proportion of the elderly population in Chinese society, leading to a multi-layered impact on the social and economic system.

1. Slower Growth and Shrinking Labor

The negative impact of population aging on economic growth is a consensus in academia. Some research has found that in China, every 10% increase in the population aged 65 and over reduces per capita GDP by 2%. The impact pathway primarily consists of two factors:

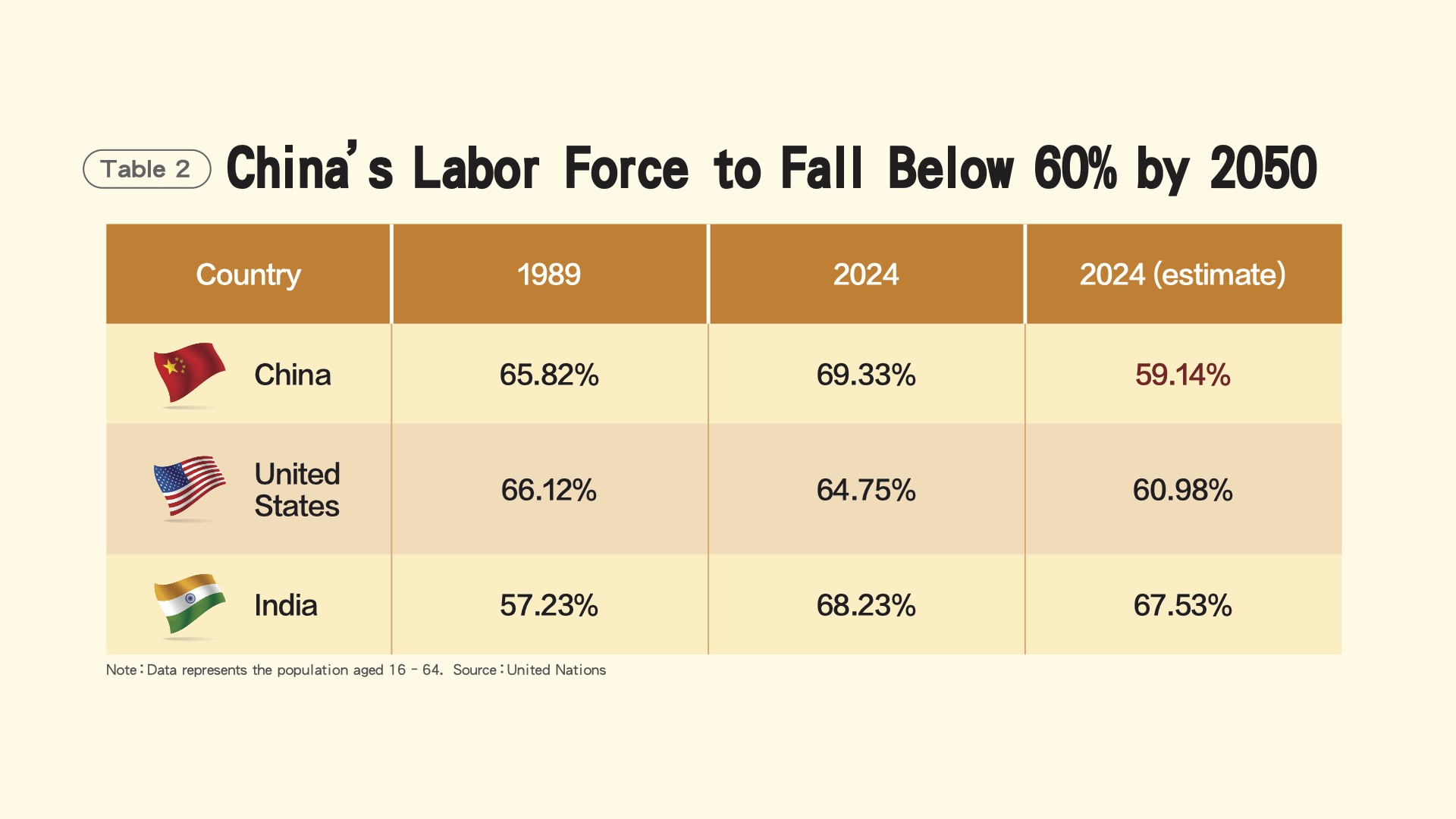

• Labor Force Shrinkage and Productivity Decline: The young and middle-aged labor force is the engine of economic development. However, the proportion of China's population aged 16–64 is expected to drop significantly from 69.33% in 2024 to 59.14% in 2050 (Table 2). In contrast, the United States and India are estimated to maintain a labor force share of over 60% in 2050, with India as high as 67.53%. The rapid decline in the labor force proportion means a significant shrinkage of China's future labor force. If this cannot be compensated by technological innovation or an increase in human capital, productivity stagnation will be inevitable.

• Weakened Consumption Power: Children and the young/middle-aged are the two groups with the strongest consumption power. The reduction in the population of these two groups means that the overall social consumption power will weaken. If retirement protection is inadequate, elderly households will further reduce consumption to cope with life in old age.

2. The Middle-Income Trap Tightens

The demographic structure of "not yet rich, already old" with a low fertility rate, makes China more likely to fall into the "middle-income trap" as its economic growth slows. The "middle-income trap" refers to a situation where a country, after reaching middle-income levels, fails to successfully transform and upgrade its economy (e.g., lack of innovation, productivity stagnation, institutional rigidity), leading to long-term economic stagnation and an inability to smoothly transition into the ranks of high-income countries. China's Gross National Income (GNI) per capita in 2023 was $13,390, placing it in the middle-income bracket defined by the World Bank. This demographic crisis undoubtedly exacerbates the challenge of crossing the trap.

3. A Looming Pension and Fiscal Crisis

Population aging puts immense pressure on the fiscal system. First is the rapid increase in the need for elderly care. China's population aged 65 and over is projected to increase from 203 million in 2024 to 410 million in 2050, a figure equivalent to the combined populations of the United States and the United Kingdom. Although elderly care in China currently still relies heavily on the family, as the size of the elderly population expands and the low birth rate intensifies, the government's long-term care burden will increase significantly. The plight of "no one to care for the elderly, no money to care for the elderly" is particularly prominent in rural areas.

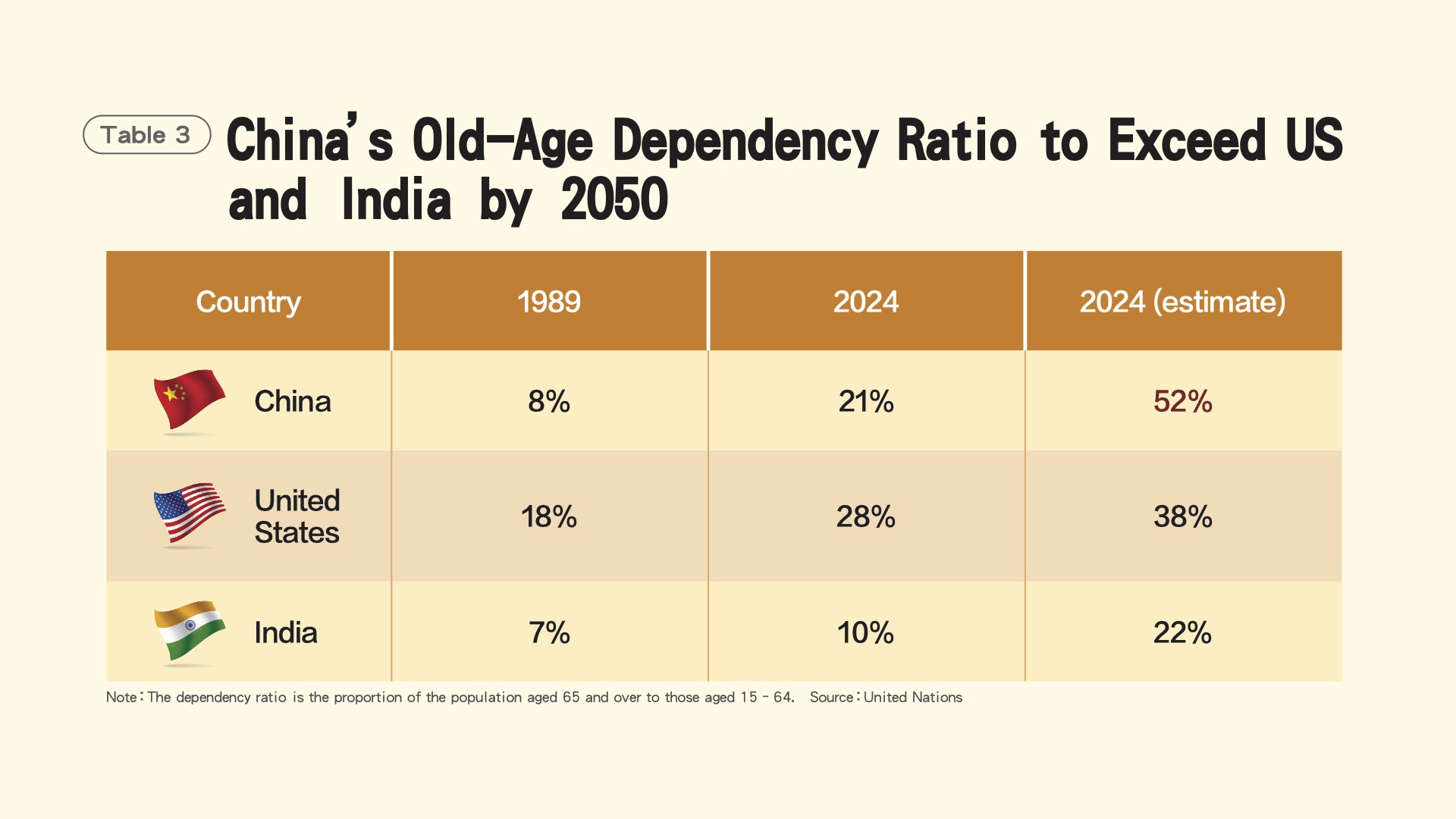

Second is the inability of the pension system to meet expenditures. China's pension system (social security) is a "pay-as-you-go" system, where the social security contributions paid by the current working population fund the pensions of the current retired population. However, with the rapid rise of the old-age dependency ratio (projected to increase from 21% in 2024 to 52% in 2050), a situation where "2 working people support 1 elderly person" is imminent, and a pension crisis where expenditures exceed income is about to erupt.

4. A Society Losing Its Edge

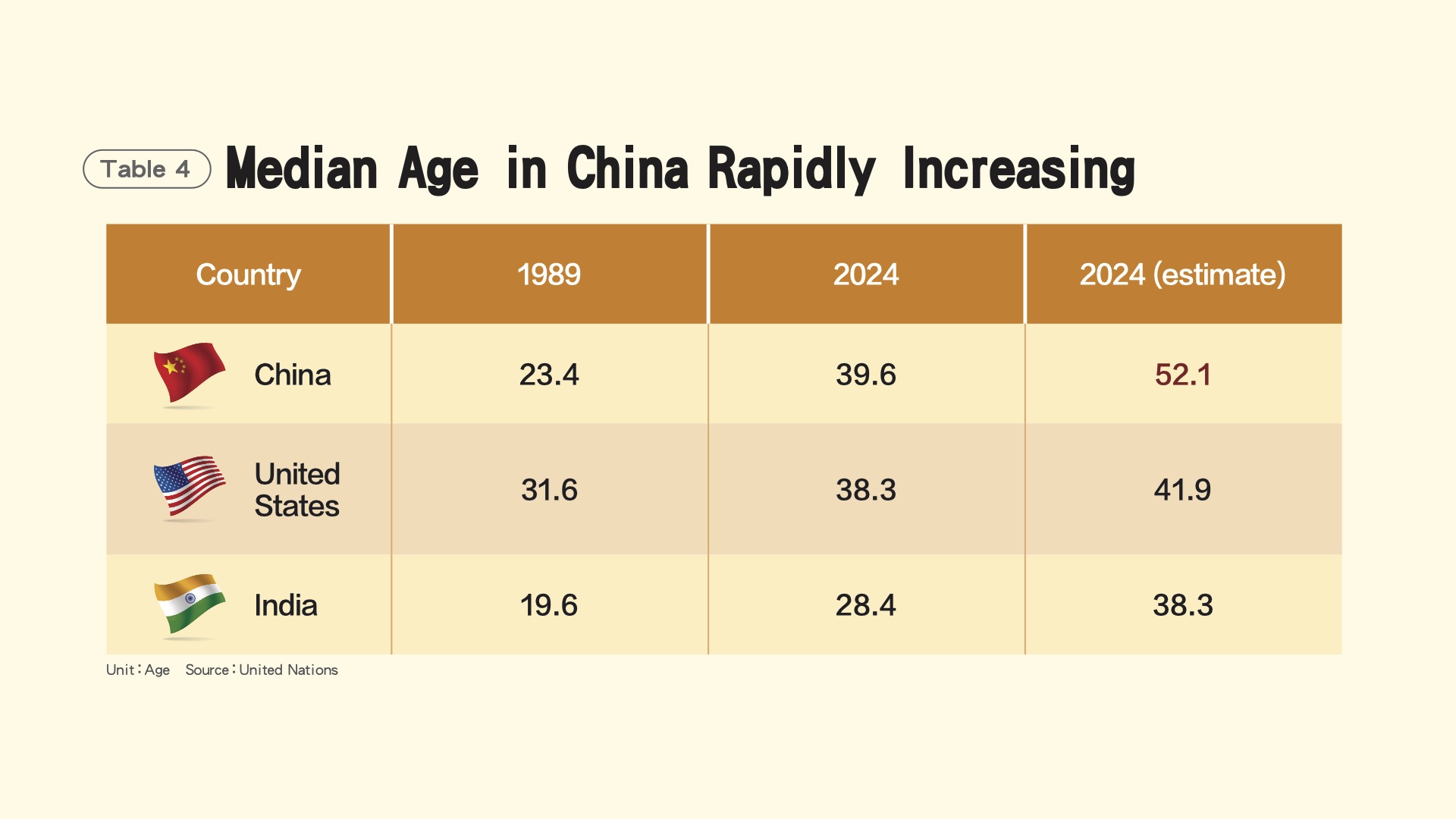

Population aging not only affects the economic dimension but may also impact social innovation vitality and political transition. Table 4 lists the population median ages for China, the United States, and India. A lower median age indicates a younger, more dynamic society. In 1989, China's society was predominantly young. As the population median age continues to rise (projected to increase from 39.6 years in 2024 to 52.1 yearsin 2050), the conservatism of society may strengthen, while the vitality of innovation and entrepreneurship may decline.

This change in demographic structure may cause China to face greater resistance when encountering political system reform or social change; the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests will be difficult to replicate. Compared to the aging China of 2050, India will be a younger, more dynamic society. The Asian economy that can counterbalance the United States may, by then, not be China.

The Strategic Implications of Demographic Decline

Facing the increasingly severe population crisis, the Chinese government has recognized the seriousness of the problem and proposed a series of countermeasures. These primarily include: (1) fully abolishing family planning policies and rewarding childbirth; (2) improving the pension system and delaying the retirement age; and (3) enhancing human capital and promoting technological innovation.

However, these measures still face numerous challenges and limitations in execution. First, the long-term one-child policy has profoundly changed the marriage and childbearing concepts of the Chinese people, leading to a resistance to having children that is difficult to reverse in the short term. Second, China's political system and national budget allocation make it difficult to invest sufficient financial resources on a large scale in population-related policies.

Changes in demographic structure are often the result of years of accumulation, and their impact is more difficult to reverse than technological blockades or trade frictions, while being more comprehensive and profound. Political economist Nicholas Eberstadt points out that "Population collapse will cause China to face a growing and potentially irremediable chasm between its ambition and its capacity". China's aging predicament is the product of the combined effect of its economic development model and birth control policies over the past few decades. This population crisis, therefore, not only tests China's policymakers but will also profoundly reshape China's future development, and its outcome will have a significant impact on the world.

(Translated by Ketty W. Chen and Nicole Wong)